Bolivar County residents share their memories

By Noel Workman & Jack Criss

The Bolivar Bullet

That day in 1994 dawned like so many February days in the Delta—cold, misty, rainy, gray. Within 24 hours, however, an unexpectedly severe storm coated much of the Delta with ice. Greenville, Cleveland, Clarksdale and smaller nearby towns were paralyzed. Electric power was cut off to more than 570,000 people in the Delta and roads became dangerous obstacle courses.

There had been a buzz for several days before the storm began.

“I was working at Delta State at the time,” said Lisa Miller, current Director of the City of Cleveland’s Martin and Sue King Railroad Heritage Museum.

“I remember so well that my eight year-old son and I went to Blockbuster Video to get the movie ‘Rookie Of The Year,’ which was a ‘Hot Release’ back then and we told the girl behind the counter that it was beginning to sleet and ice up outside. Well, that night we were watching the movie at home and around 8:30 p.m. the power went out and stayed out for about a week. ‘Rookie Of The Year’ was stuck in the VCR but I think our late fee was waived!”

At that time, Anne Martin Vetrano from Rosedale was a tv anchor on the local television station, and she told viewers to take her warning seriously and stock up on emergency supplies before it was too late. Signing off her dinnertime newscast back then she said the storm would probably start in about 20 minutes.

“We all knew from the weather reports that a storm was coming, but we had no idea of the severity and the devastation in store for us,” said Danny Abraham, owner of Abraham’s. “No electricity, no water and no communication for days. This storm was considered as the second worst ice event in Mississippi history–but I’m afraid the next ice storm will be even more disruptive. We are now more dependent on cell phones for communication and daily activities. I pray, though, that it never does happen again.”

Deltans are nothing if not resourceful. No electricity during the event meant that generators were highly prized. Those with enough foresight to have one were saluted by their neighbors. Except in Ruleville.

“My brother Jeff, and my father, Billy, made a trip to Alabama to pick up some generators,” said Dean Nassar, who lived just out of Merigold. “At the time, Jeff worked for the Leland Police Department and was told by a lady there who worked at a hardware store that a supplier in Alabama had three or four generators left. When Jeff got off his shift that night he and dad drove all the way to pick them up early the next morning. I kept one, Dad and Jeff each got one and we gave one to Dr. Gene Coopwood’s dental office in Shelby. I remember the ice storm completely destroyed the 40-acre pecan orchard in our backyard that we had bought the year before–that was the worst thing that happened to us.”

Although no names were ever attached to the story, the tale of a Ruleville generator owner was widely told and retold. Seems that he was enjoying his do-it-yourself electricity and had become accustomed to the constant diesel motor hum of his generator. Awakened in the middle of the night, something seemed amiss. The hum of the motor sounded a bit different, but it soon lulled him back to sleep. It was the next morning before he realized that his prized generator had been stolen and the enterprising thief had cranked up his lawn mower in its stead.

In the days following the storm, people rushed around gathering supplies before dark—remember, no street lights or traffic signals—and the streets were deserted by dusk, with candles in the windows of homes for lighting.

Greenville’s Sunflower Food Store had a line waiting to get in, three at a time, into the dark store with no electricity for ice, charcoal, water, whatever food was handy and cigarettes. No power meant no lights and no cash registers. Store owners had to trust their customers—and very few merchants were disappointed.

“The discomfort and the stress levels were pretty high,” recalled one Greenville woman, requesting anonymity, even 27 years later. “We were all so stressed.”

She should know. She made the front page following her arrest for firing a gun to get the attention of laborers whose method of collecting storm-damaged tress was to drag them through (and damage) her trees, which had somehow survived the ice. “It was more than I could take. I ran out in my pajamas and fired the gun in the air to get their attention,” she said.

When Greenville City Judge Earl Solomon reminded the woman that any bullet fired up in the air must come down somewhere, “I know, Judge,” she said. “That’s why I fired over the cemetery.”

Evidently the judge failed to see the irony of the defendant, who lived very close to the Greenville Cemetery. She paid more than $900 in fines.

Many Clevelanders especially remember the sounds and smells of the storm period. The cracking and falling of tree limbs and the snapping of utility poles dominated the first couple days, followed by weeks of the roar of chain saws and the whining of generators. The smell of food was frequently in the air as folks rushed to salvage the contents of idled freezers by cooking on the most readily-available source, outdoor grills.

Many chose to keep food in coolers outside on their porches and offered any extra food to their neighbors. Bolivar Coutians quickly learned to live like pioneers.Without power, freezers stopped freezing. As food began to thaw some churches hosted huge potlucks for any taker. Across the Delta, the Red Cross opened 27 shelters for 2,719 people and served 34,929 meals. The Salvation Army also had 27 centers and served 118,531 meals.

The ever-hospitable Hank Burdine who lives South of Greenville and is often a contributing writer to The Bolivar Bullet remembered, “My meager helping hand came at the hands of our local bootleggers,” said Burdine. “I bought cases of Peach Brandy half-pints and tossed ‘em up to the workers in the bucket trucks and on the ground. It was cold!”

Wayne Nicholas, managing editor of Cleveland’s Bolivar Commercial at the time, said in an old interview with Delta Magazine that, “It looks like Mother Nature made a bombing run.” The Bolivar Commercial and Greenville’s Delta Democrat-Times were without power and had to use the presses of The Greenwood Commonwealth because Greenwood escaped much of the storm and thus had electricity.

“We only missed putting out one edition of the paper during the whole event–the very first day after the storm,” said Denise Strub who was the Lifestyles Editor of The Bolivar Commercial at the time. “I think we had a generator, two computers and a fuel lamp in the front office–we also had candles and flashlights in the back. Norman Van Liew, the publisher then, was adamant that we get the paper out and we did. We were out of power for at least a week at the paper but some people went even longer. A few of us on staff camped out at Mr. Van Liew’s house during the whole ordeal, cleaning our clothes with his washer and dryer which was hooked up to a generator.”

An estimated 26 million trees along streets and highways were destroyed in the 26 north Mississippi counties affected. Half of the state’s pecan crop was lost.

It was the largest, most costly and longest power outage in the 71-year history of Entergy or, more precisely, Mississippi Power & Light. We lost 25,985 power poles, leaving 350,000 people without power for an average of seven days. Most in Shelby and other outlining towns were without electricity for three weeks.

All five transmission lines from the MP&L power plant in Cleveland were down, darkening the Delta for miles around. Nineteen thousand miles of power lines were replaced by M&PL and the help of 2,500 additional personnel from eight other states. South Central Bell replaced 1,600 poles, calling on 275 phone crew members from eight other states. More than 51,000 SCB customers lost service with the 46,000 dropped lines.

Three months after the storm 13,000 insurance claims for $15 million had been filed. There was also an additional estimated $10 million in costs to homeowners who were not compensated for debris and tree removal.

“The freezing rain started the night of February 10, 1994,” said Ned Mitchell, former Bolivar Insurance and SouthGroup CEO. “By morning, it looked like a bomb had hit the city. We tried to open our office that morning, which was then Bolivar Insurance, but we couldn’t. On a personal note, the Winter Olympics were on the next night and my son-in-law, Keith Bailey, got a generator so we could run the TV and watch with some of our neighbors! People started lining up outside our office the next day with their claims and we had a small generator and a heater inside. We had everything coming in, from roof damage to meters coming off of houses. But, our largest number of claims, believe it or not, was for spoiled food.”

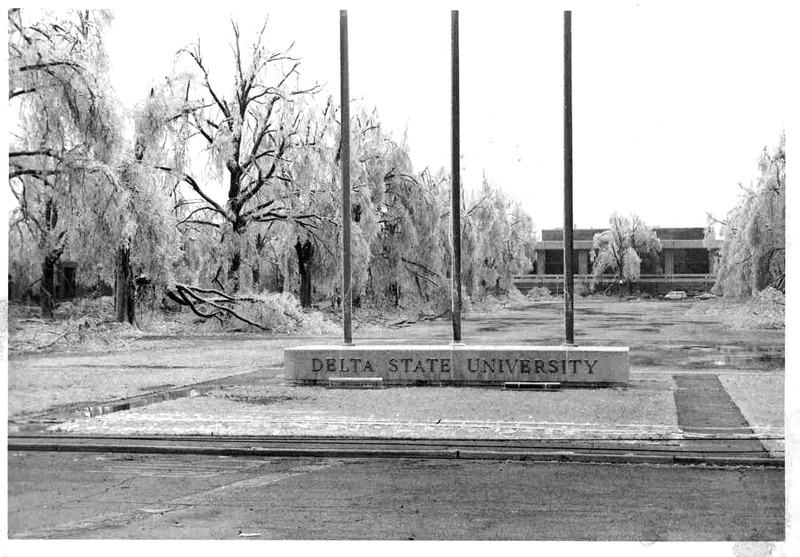

“I was actually in Jackson when the storm hit, at an IHL Board meeting,” said Dr. Kent Wyatt, former President of Delta State University. “And, I had no way to communicate with people in Cleveland. Our business manager at Delta State at the time managed to drive to Greenwood to reach a cell tower late that night so that he could call to let me know what was going on. Driving back the next day, coming into Cleveland, I was confused: Even after growing up here, the devastation was so bad I had a hard time figuring out exactly where I was. I was told that, when the big trees in the campus quadrangle started falling, it sounded like cannons going off. It took two weeks before classes could resume.”

The stats go on and on. As did the destruction. At $73 million, it was the largest and costliest disaster in MP&L history.

The Delta’s new landscape was marred by scraggly stumps and barren parks and streets with no canopy of shade for many years. All in all, it was an epic ice storm for the record books.