A quiet spirit with a colorful soul

By Katie Smith

The Bolivar Bullet

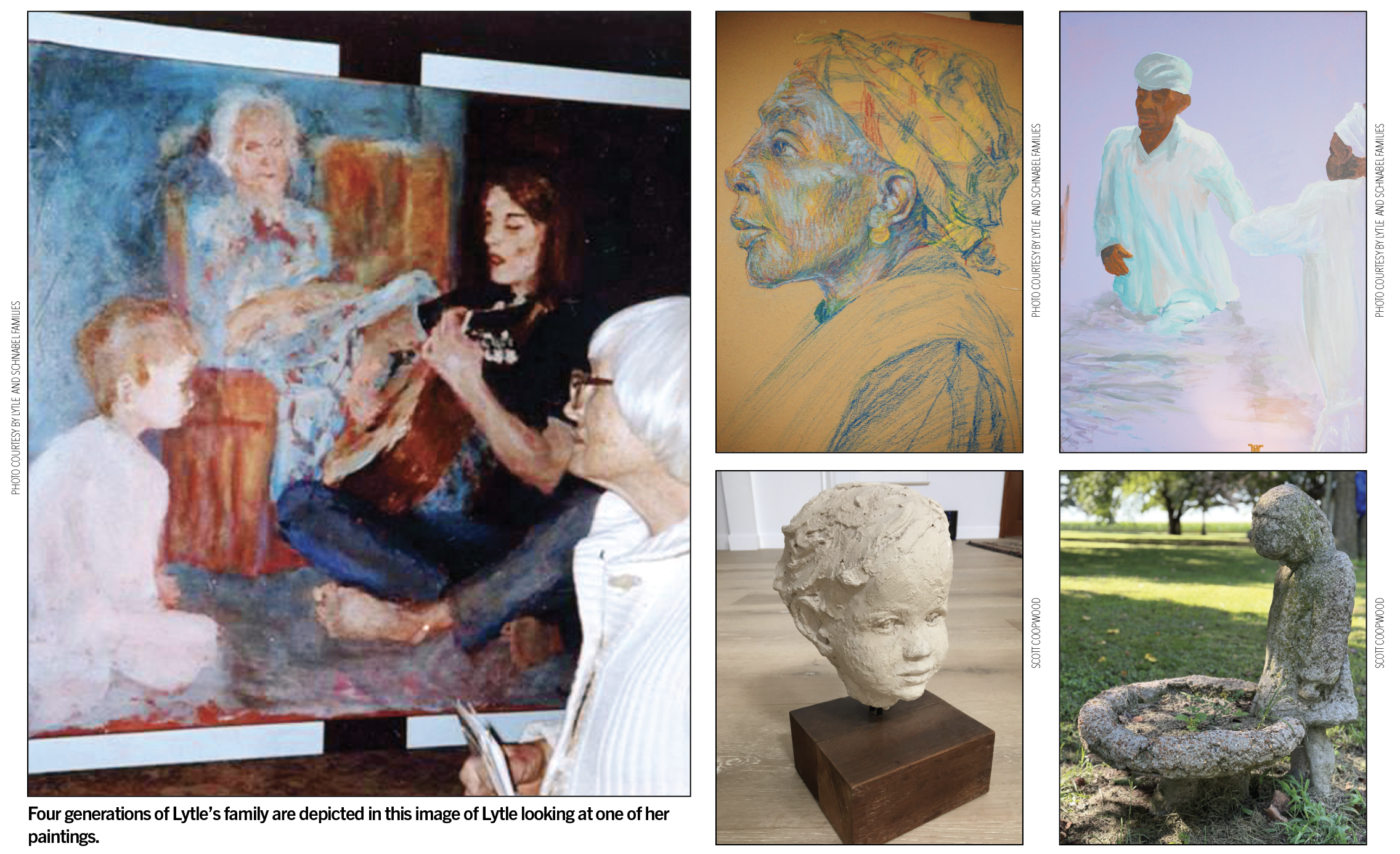

The late Bolivar County artist Emma Knowlton Lytle who passed in 2000 was the type of person who made an impact on anyone she met. Lytle, who lived in Perthshire just north of Gunnison, is still remembered fondly by friends and family and the stories told of her life are vivid. A painter, sculptor, poet, and even a film maker, Lytle’s works, especially her paintings, can be found at Delta State University and on the walls in many homes around Bolivar County.

Lytle was born in 1910 and grew up in her family’s home in Perthshire. She attended Sweet Briar College in Virginia then transferred to Radcliffe College in Cambridge, Massachusetts the women’s college that was part of Harvard.

She married Jack Humphreys and had her first daughter, Eleanor, when the family lived in Mississippi.

One of the first times Eleanor can remember seeing her mother work, was painting backdrops for the model train set that her father Jack built.

Unfortunately, Lytle was widowed at a young age, and took her daughter back to Perthshire where they lived with Lytle’s mother.

Eleanor said her mother had bad attacks of hay fever and asthma so they moved to Albuquerque, N.M. for six months. While there, Lytle was introduced to Maria Martinez, a Native American famous for her pottery. Just like her interest in pottery, Lytle was involved in just about every form of art, including film.

“They all got 8mm Kodak cameras just before World War II,” said Eleanor. “It was like people buying Polaroids in a later day. My uncle Buddy had one as well. They all made movies and mother just decided she wanted to tell the story of growing cotton, and that’s what she did one whole year on film.”

That film, entitled, “Raising Cotton,” is a work of art and is housed at the Center for the Study of Southern Culture at the University of Mississippi in Oxford. The film can also be viewed on YouTube.

Emma eventually married Stuart Lytle and they moved to Chicago and had son, Bob, and daughter, Susan. Lytle was a housewife and helped her husband with the bookkeeping for his business. While living in Illinois, she took classes at the Art Institute of Chicago and a satellite campus of Northern Illinois University.

However, art wasn’t the only area that Lytle dove into headfirst. She also had a great passion for politics and religion — things women of her generation weren’t necessarily always interested in or encouraged to be involved in.

During the period of 1956 into the early 1960s, around the time the National Guard enforced integration in Little Rock, Ark., Lytle made her voice heard.

“She went on a letter writing campaign,” said Lytle’s son, Bob. “She was really quite political. She founded The Women’s Republican Club of Ogle County in Oregon, Ill. I can remember Everett Dirksen, one of the two senators from Illinois, spending the night at our house. She was very active. The important part of that is her writing letters to prominent Mississippians, probably prominent Deltans, about the ultimate need to change the traditional ways of the Delta in regard to relationships with blacks.”

Lytle received letters back stating everything from agreement to, “mind your own business.”

In August 1966, the Lytle family moved back to Perthshire.

Around this time, her children remember Lytle delving into what would become her most famous artwork, scenes of African-American baptisms.

“I think a spark was her relationship with a black minister, named Tom Bronner, from the Delta, who preached at one of the small frame, one-room black churches at Perthshire. They became good friends,” said Bob. “She was filming and painting the baptisms as early as 1937. She filmed these baptisms, then she had a machine where she could look at the film frame by frame and she’d pick a frame that she particularly liked, for the composition primarily, and she would have it blown up and printed. These were blown up into little prints, then she would expand the composition by using rectangles. She would sketch a larger version of it and then sketch the composition, then paint it.”

These particular paintings were scenes close to Lytle’s heart. She recorded a life and time period in the Delta that is now mostly non-existent.

“Probably because it was such a strong expression of her own Christian belief, and it was just part of what she believed and believed with them,” said Eleanor. “I know part of it was to honor the importance of all African-Americans. They were like members of the family; to honor them in our lives, the part of their lives in our lives. Out at Perthshire, we were all members of the same family. Mother always had a great deal of appreciation and thankfulness for their part in our lives.”

Lytle’s return to Perthshire and the Delta only increased her love for the place she called home.

“She painted murals of cypresses and of her memories of the Delta on the dining room walls,” said Bob. “There were these large plaster panels that she painted with scenes from the Delta.”

As she grew older, Lytle maintained a visual presence with her short white hair and habit of almost always dressing in the color white. She was articulate and remained dedicated to her art.

Lytle never stopped making friends; because it was easy for her.

“She was just a natural, she saw art in everything,” said friend Cheryl Line of Cleveland. “I treasure her paintings that I have as much for just having the memory of her as the artwork. She was an artist at heart, just the kind of person you want to be around; always upbeat, delightful. Her house was an oasis, an absolute oasis, for those of us that loved her.”

Lytle had a studio in her Perthshire house and would tell stories about growing up there and the plantation system. She was well educated and well read and beyond her spirituality, Lytle had a special view of life.

“She talked about how the past and the future are but figments of our imagination and that life takes place in the moment,” said Bob. “In her 70s and 80s, she would get excited, like a child in some ways, talking about that. She really got that.”

“She had a quiet nature that kind of helped you settle down after we go so fast in this life,” said Line. “Her house was a place to take a deep breath and relax.”

Lytle’s legacy isn’t just in her paintings, sculptures, films, photographs and poems.

She left a lasting impression on her children too, who fondly remember helping her cast heads for her sculptures.

Lytle lived a full and productive life. She was a beautiful person in many ways and a mentor spiritually. She will always be remembered for her works of art that paid no mind to the color of a person’s skin.

Editor’s note: for more on Emma Lytle, visit www.mississippiemma.com.