One of Bolivar County’s most notorious stories.

Al Capone considered Perry Martin’s moonshine the best there was. He sent specially designated boxcars with armed guards down to Rosedale from Chicago to load cases upon cases of what was known as PM. To those who remember it, PM was arguably the best moonshine in the country.

In any speakeasy in Chicago, New York, Pittsburgh or New Orleans, all you had to do was ask for “PM” and you were given the finest moonshine whiskey there ever was, straight from the riverside of Rosedale, Mississippi. There are heirloom bottles today that are passed down from generation to generation, with a sip taken on special occasions. Judge Bard Selden from Hollywood, Mississippi, recalls his father telling him, “Each month, you could set your watch by the arrival of a long black Twin Six Packard limousine with District of Columbia plates headed south on old Highway 61. Later that afternoon, it would make its return trip to Washington, D.C., through Hollywood, loaded, with its rear fenders low to the ground. Franklin D. Roosevelt was the President back then.”

During the days of Prohibition, moonshine was made in back country stills all over the South. Federal revenuers were kept busy locating and busting up illegal whiskey stills and carting off those that got caught to jail. Even though Perry Martin was fined a few times, it is doubtful he ever went to jail for making moonshine. It was illegal to make whiskey within the city limits of Rosedale, those limits extending across the levee and to the river. The offense carried a $100 fine. Martin paid his fine in advance each year on January 1. The late Mr. Charlie Capps, who was sheriff of Bolivar County during the last years of Perry Martin’s life, once recalled, “I would receive a gallon of PM each year around Christmas, and I never even met Mr. Martin.”

Martin was the son of a wealthy rice farmer and had been educated for the ministry. As a young man he was involved in state and local Arkansas politics. In 1920, he left the rice farm with his wife and two children and settled on Big Island, a 121,000-acre wilderness area across from Rosedale at the confluence of the White, Arkansas and Mississippi Rivers. He went into the timber and logging business. Big Island was reported to be the “largest whiskey producing area in the United States.” Earl Drury, a retired moonshiner from Big Island that served 12 years as Rosedale’s Constable, said that when he sat in front of his still on Big Island he could see an additional 21 stills in operation. When asked if life was dangerous on Big Island, Drury recalled, “There was plenty of law and order on Big Island. Simply, if there was an argument, somebody got killed.”

According to Drury, the main law enforcement figure on Big Island was Perry Martin himself. The sheriff of Desha County, Arkansas, had sworn him in as a deputy and he wore the badge with pride.

Not many people bothered Martin because he had the reputation of being a violent man. This was possibly untrue unless he was provoked. One hot summer night he was guarding a raft of his own logs tied up on the river awaiting a boat to pick them up. Five men came up with guns and tried to steal the logs. A gun battle ensued and Perry Martin killed all five of the robbers. He turned himself in to the sheriff’s office and was acquitted for “simply protecting his own property.” It is also believed he killed his own stepson during an altercation. According to Henry McCaslin, Perry Martin and his stepson were in a rowboat in the river and the stepson started rocking the boat, either to try to throw him out of the boat or to just scare him. “Perry Martin pulled his pistol and shot him because he could not swim.”

Melvin Martin, Perry Martin’s grandson says, “My grandaddy was a very educated man. He was an ordained minister, a self-made man, and he was as good as gold. But, if you crossed him, he would kill you.”

After killing a man for stealing his hog and only serving one year of a 10-year sentence, Perry Martin gave up logging and went into the moonshine business. He moved to the east side of the river in 1929 and lived on the banks of the Mississippi in a fairly ornate old wooden houseboat set up on blocks in a grove of cypress trees. In 1950, Martin bought his wife, Lou a house at the foot of the levee in a place called “the pasture.” He spent the first night in the new house with her and became ill and was not able to sleep. He never stayed another night on the dry side of the levee. Yet each day he could be seen walking across the levee to have lunch with his wife. He slept on his houseboat every night to be close to his stills.

Will Gourlay remembers that as a boy growing up in Rosedale, camping and hunting on the river, he would often see Martin.

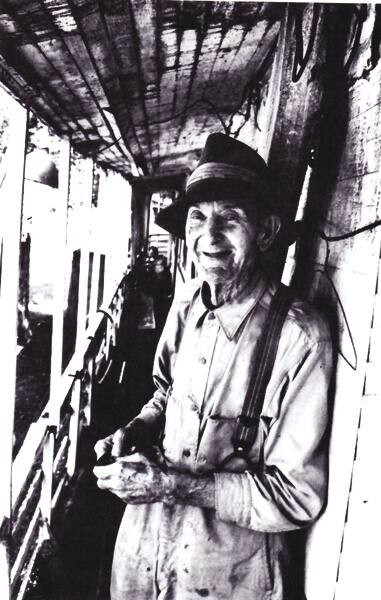

“Mr. Perry was a tall and slender man. He walked slowly and he talked slowly, making sure you heard and understood everything he was telling you. He drove an old green Jeep pickup truck and you never knew where you might see him along the river. He had stills all over those woods.”

According to Martin’s daughter-in-law, Mrs. Myron Martin, “one of the most frightening things about him was that you never heard him in the woods until he was face to face with you.”

Bill Parker says that according to Alfred Welsan, “each time you went out to the houseboat to buy a gallon of moonshine, Martin would have you come in the kitchen where he would pour you half of an iced tea glass of PM. You were expected to drink it right then and there to ensure its quality. With the heat of summer, and no air moving at all in that sweltering houseboat, after you drank your sample and paid for your gallon, it was all you could do to make it back up to the top of the levee!”

The whiskey did not have the crystal-clear appearance of most moonshine, otherwise known as white lightning, because it was aged in oak barrels giving it a deep amber color and wonderful tannin flavor, much like good bonded Kentucky bourbon. There were wooden kegs of PM buried all over the woods, their secret whereabouts known only to Martin himself.

There were several reasons for the quality of Perry Martin’s whiskey. Using the basic Kentucky recipe, one part corn to one part sugar, he adjusted and blended rye malt in with the corn. He got his water right out of the Mississippi River. His stills were pristine and immaculate with the bright copper works glistening in the sunlight filtering through the tall oak trees. He always made small batches and cooked it very slowly. Yet according to some, the most important thing was the use of white oak barrels that “rocked gently under willow trees by the ebb and flow of the Mississippi River along its banks.”

At 90 years old, Perry Martin made his last batch of whiskey. He had just built a brand new still and run off his first batch when he was raided and his still destroyed. In a moment of frustration he got out of the business that had made him famous all over the country.

He suffered a stroke and died on September 9, 1968.

Perry Martin has been remembered as a good man, often giving his money away freely to those in need. He raised a little girl who had been abandoned on a shanty boat and sent her to college. He reared another young man outside of his family. Martin entertained visitors, customers and politicians alike, often telling humorous stories.

Martin did not fit the local vernacular of a “river rat,” according to William Alexander Percy in Lanterns on the Levee, “illiterate, suspicious, mean, clannish, blonde and usually ugly.”

Perry Martin was well educated, honest, proud, generous, self-confident, self made and independent. He may have spurned genteel society, yet he demanded its respect. He has been recorded in history as the most famous moonshiner in Mississippi, and very possibly, of all times.