Deep in the Delta’s alluvial soils, archeologists are seeking to unravel the mysteries of Hernando de Soto and the chiefdoms he encountered—before it’s too late.

By boyce upholt

The Bolivar Bullet

Most of the men were out working in the corn fields that day, so the village plaza was undefended. A few hundred women remained behind, watching the children and preparing meals.

The invaders were like nothing they had seen before: wrapped in strange gleaming shells, they had the torsos of humans, but grafted atop four-legged beasts. The only thing clear about them was their anger.

Most of the villagers fled into the woods and swamps outside the town, but their chief—ancient, fading, too weak to even hurt a dog—retained his old fury. He grabbed his war club and began to descend his temple mound. His wives and servants clung to him, begging him to yield. He was too old, and these strange new wrathful men were too strong.

Looks, though, could be deceiving. Those men—the army of Hernando de Soto, Spanish conquistador—had suffered a demoralizing defeat. They had limped for nine days through a vast, swampy jungle. Their ferocity was mere bluster.

This village was a part of a chiefdom known as Quizquiz, or at least that’s the name that de Soto’s army recorded. The villagers have left no notes, and perhaps this is why the story is so often told from invaders’ point of view. According to local archaeologist John Connaway, the Indians they encountered fought back in their own unique way—often through cleverly providing misinformation.

De Soto sought gold. Some of the chiefs convinced him he’d find it—if they went looking in the next village over. Predictably, when de Soto got to that next village, “they’d say the same thing,” Connaway explains. “So old de Soto, he didn’t fare too well.”

He did win fame: parks, schools, towns, counties—they all bear his name, as does a now-defunct line of Chrysler cars. He is universally recognized for his “discovery” of the Mississippi River. His army found it soon after raiding the Quizquiz village—though, of course, considering that there was a village there to raid indicates that the river was already well-known.

Indeed, life in ancient Mississippi depended on the river. The river supported the land; the river created life. Its adjacent swamps were filled with fish and berries, and the surrounding alluvial soil was rich for growing corn. Upstream, near modern-day St. Louis, the great city of Cahokia had emerged in the river’s bottomlands around AD 1050, becoming the largest prehistoric metropolis north of Mexico. Three centuries later, though, when de Soto arrived in America, Cahokia was in decline.

No white man would see the river for another one hundred forty years after de Soto’s arrival and departure, a span that would lurch the world towards modernity. Interestingly, de Soto’s men were mostly medieval: you might picture a horde from Game of Thrones. Seven hundred strong when they embarked from Spain, many were kinsmen from a single province. Their bodies were sheathed in armor and—while carrying rudimentary guns—they fought mostly with crossbows, lances and swords.

De Soto was known to make decisions quickly, perhaps too quickly. He had little patience for foolishness. He sought wealth and power, whatever the means—murder certainly included. He was of noble birth, but not rich. He built his fortune as a young man in Central America, often by slaughtering and enslaving the locals he found.

In Central America, de Soto was essentially a junior officer—but he was ambitious and wanted to command. He returned home to Spain and begged permission to conquer “La Florida.” When the king agreed, de Soto began to assemble his army.

They landed in Florida in May 1539, and from the start suffered. Ambushes were constant. In one nine-hour battle in Alabama, nearly half the army was killed or wounded. The damages they inflicted were worse. As many as 6,000 enemy warriors were killed, making it one of the bloodiest conflicts ever recorded on this continent. After a long winter, de Soto’s army suffered a small but demoralizing defeat near modern-day Tupelo.

De Soto was still recovering from that defeat when he arrived in Quizquiz, in the Mississippi Delta. Still, the Spaniard managed to triumph. While the old chief’s wives and servants convinced the old man not to attack, he did spit his fury at de Soto even as he was being taken captive.

How true is the story I tell you? It’s hard, really, to know. There are four historical chronicles that recount the exploits of de Soto and his men. One account is heavily romanticized, written long afterward, based on interviews with survivors. The chiefdoms de Soto’s men encountered have no written record of their own. Our knowledge of these battles is pieced together, often by matching notes from the chronicles with artifacts that archeologists manage to pull from the earth.

John Connaway, a retired survey archeologist for the Mississippi Department of Archives and History, explains the weakened state of the expedition when they entered the Delta is part of the challenge of recreating their path.

“By the time they got here, they were kind of depleted,” he said. The little cargo they had was precious; they weren’t about to cast any of it aside. That means there is little for archeologists to exhume.

One halberd was found in Leflore County, and a second one of similar make was found just across the river in Arkansas. These were weapons carried by the Spaniards, polearms outfitted with a versatile array of weaponry: a spear-tip for stabbing, an axe-head for chopping and a hook for pulling an enemy off a horse. Experts believe both likely came from de Soto’s army.

a version of the De Soto Expedition route, by Charles Hudson and Associates, 1991

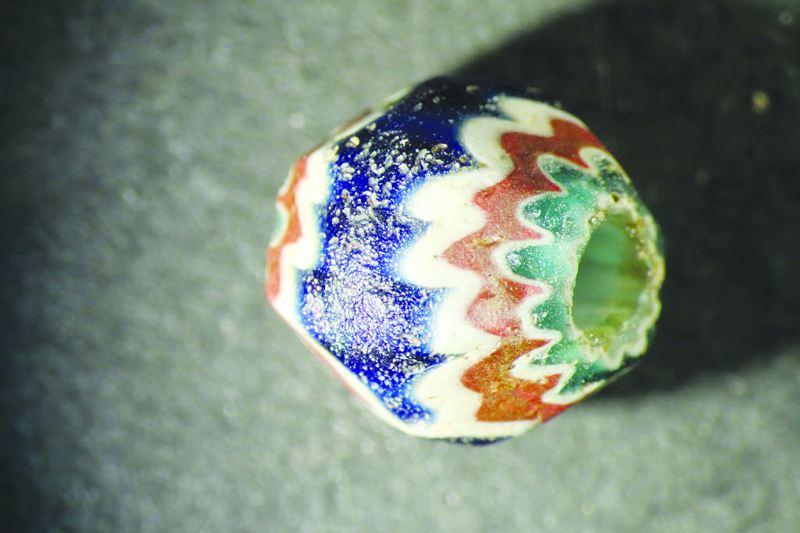

layered glass chevron bead recovered from the Parkin site in Arkansas is another artifact believed to be from the de Soto expedition

reproduction Spanish helmets on display at Parkin Archeological State Park

A halberd was a type of weapon carried by European foot soldiers. De Soto’s men carried halberds. This halberd was found in Schlater, Mississippi and it is on display at the Museum of the Mississippi Delta in Greenwood. Scholars believe it came from the de Soto expedition.

De Soto’s secretaries kept meticulous notes on their journey throughout the South. These accounts were turned into the book, The De Soto Chronicles, Volumes I and II. This material has been invaluable to historians and scholars in their pursuit of the de Soto story.

Small brass bells found at an Indian mound near Clarksdale are presumed to have come from the expedition, too. These bells were carried as trinkets for use in trade. It’s more likely, though, that the Clarksdale bells originated from other Spanish travelers in the far Southwest and were carried here by intercontinental trade. Nothing found in Mississippi, not even the halberds, has been indisputably tied to de Soto’s expedition.

What is indisputable is the centuries long presence of native cultures. People have lived in the Delta for thousands of years—long enough to leave plenty of trash and plenty of clues to their lives.

As the river has shifted its course over time, it has deposited soil containing many hidden native secrets—and protected those secrets too. Their potsherds and food scraps are buried in mud, waiting for archaeologists to piece together their story.

These clues reveal a complex society, as politically complicated as late-medieval Europe. Most Indians lived in small villages, often three to five hundred people. Some residents might never travel more than a few miles beyond their home. Groups of villages were linked into larger chiefdoms, each led by a supreme chief who was often said to descend from the sun.

The sickly old chieftain who was captured by de Soto, for example, was himself under the dominion of a more powerful ruler. This chief scoffed at de Soto’s bluster. He demanded the prisoners be released and de Soto, with so many men wounded, decided it was better not to fight.

For the next few weeks there was something of a détente, with small raids but little protracted violence. De Soto’s men managed to find the corn they needed and some pecans (an unfamiliar nut they quite enjoyed). They set up camp so they could build boats to cross the great river.

This camp was constantly harried. Almost every afternoon, a fleet of canoes arrived, the warriors hollering. They paddled close enough to shoot arrows. From foxholes, de Soto’s men volleyed back. After twenty-seven days, when the boats were completed, the Indians withdrew. They, too, seemed to hope to avoid a true fight.

One night in late June 1541, at nearly 2:00 a.m., under the slim light of a crescent moon, the first men rowed a quarter of a league upstream and then pushed across the river. They unloaded on the far side without incident and the long process of ferrying the army began. Finally, two hours past sunrise, everyone had reached west bank. Today, we see this crossing as de Soto’s great accomplishment; but for the conquistador, no doubt, it was little more than a delay in their hapless quest.

To better understand how these stories are revealed, I drove to Coahoma County to a site called the Carson Mounds. It was a searing afternoon, but a small task force of volunteers stood in the sun, listening dutifully to an archeologist’s instructions. A ground penetrating radar–a contraption that looked like a computer attached to a lawn mower—was being rolled over the earth to discover what might be hidden below, a great help since there aren’t enough John Connaways around these days.

Connaway is lucky that he had volunteers there. He once spent three years working without a crew on a site in Tunica County. He had told the farmer whose land he was studying that the work would take a few months. Three years later, the farmer asked whether those months were up.

“But he’d just laugh about it,” said Connaway. “It really didn’t hurt him to leave out an acre or two.”

Meanwhile, farmers continue to level new land—bringing in heavy machinery to make the landscape even flatter, and therefore easier to irrigate. But this makes archeological digs and research much more difficult, often disturbing or destroying ancient sites and our understanding of prehistory.

“There’s always stuff out there that we haven’t found yet,” said Connaway. He points, for example, to his own insights: he once found certain rocks that suggest that a group of migrants from Cahokia lived at the Carson site.

Given the significance of Cahokia—it is the epicenter of the continent’s prehistorical culture—this is an important discovery. It rewrites our understanding of ancient local politics; for years, archeologists have thought chiefdoms in the Mississippi Delta existed largely separate from the great city’s sway. To me, it’s a moment of startling clarity: the arc of individual lives resolves to clarity, across the distance of centuries.

That’s a sort of clarity we may never have about de Soto. We do know, though, how his story ends. After the conquistador died of fever, his body was dropped in the Mississippi River, hiding his death from the army’s enemies. His men wandered west to Texas but they never found a settlement large enough to support their numbers and eventually returned to the river. They built a fleet of boats, and headed downstream.

As they left the continent, they were pursued by another fierce Deltan chieftain, the great Quigaltam. Through the night and into the next day, the Spaniards paddled hard before their pursuers finally gave up the chase.

These are the men who would survive to tell de Soto’s story. Beneath their boats, beyond their knowledge, was another story. Long after they reached the safety of the Gulf, a muddy plume continued—a remnant of the river, and the soil it carried, and the secrets it contains.