A historical area in downtown Cleveland

by Lisa Miller

The Bolivar Bullet

For several years now, I have been researching the history of our downtown, photographing the backs of the buildings, the alley, the parking lots. The more I researched, the more convinced I became that we had partially let go some of our history that had help shape Cleveland into the city it is today. I realized this unique area was worthy of a Historical Marker and the Mississippi Department of Archives agreed.

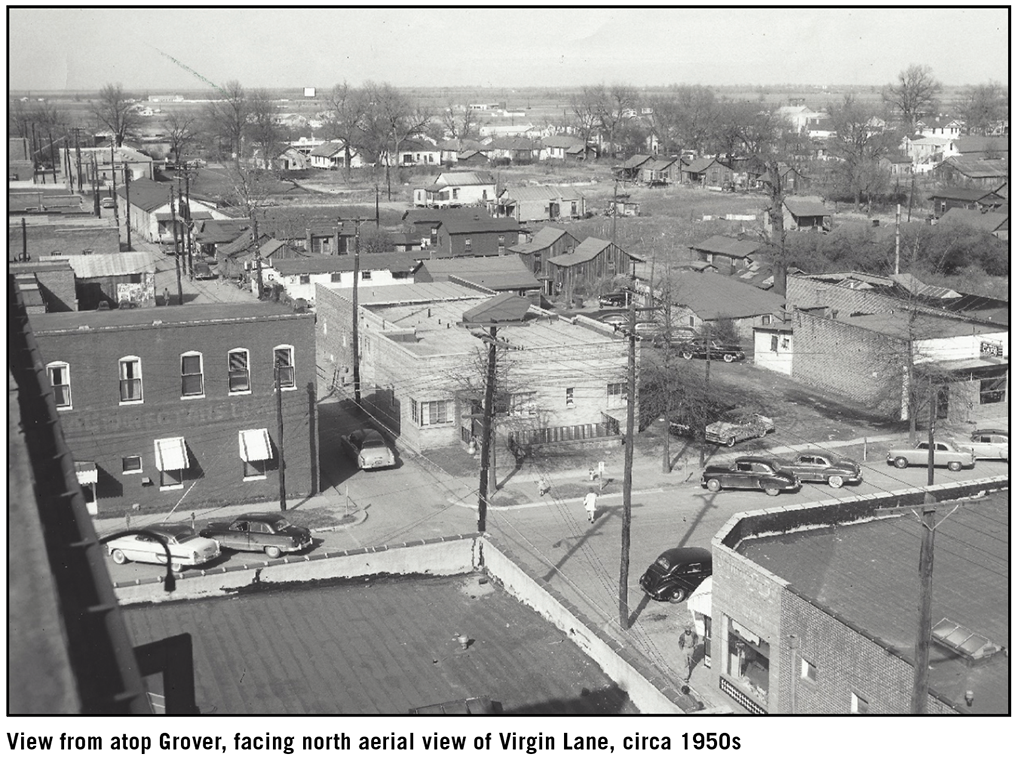

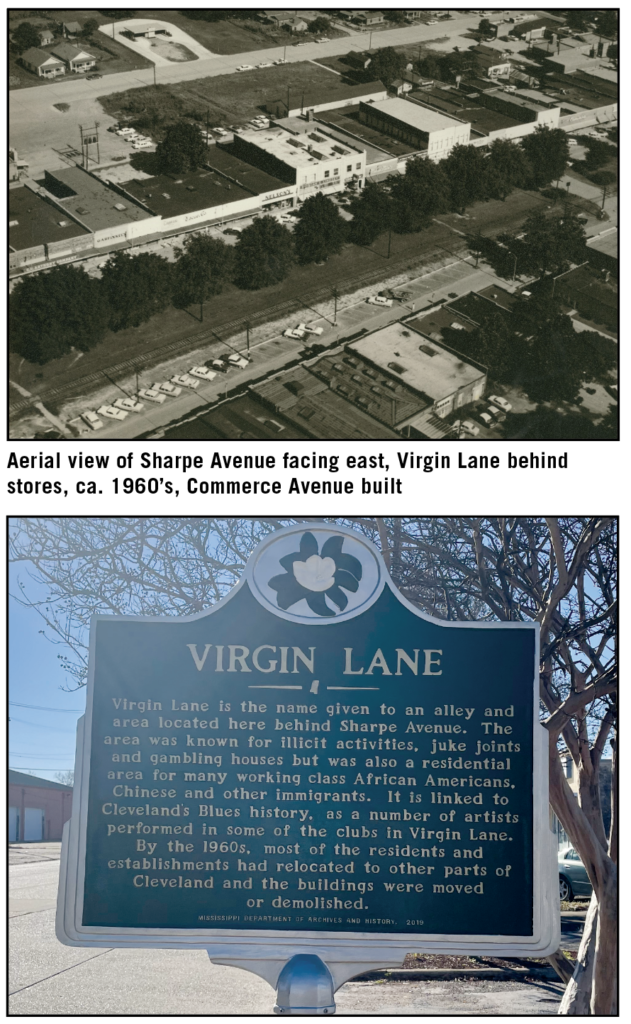

An 1885 map of the “Town of Coleman” shows the layout of downtown was then very much like it is today, including the alley on the east side of the Sharpe Street buildings. In 1886, Coleman became Cleveland and as we grew the alley grew as well. Virgin Lane was the name given to the alley and the area that was behind the stores on Sharpe Avenue. This area was once bordered to the North by Highway 8, to the East by Chrisman Avenue, to the South by South Street, and to the West by the continuous alley that ran along the back doors of the Sharpe Avenue merchants. As time went on a mixed use, multi-ethnic, and sometimes boisterous neighborhood developed in that sort of boxed-in area surrounded by well-traveled thoroughfares through town.

The origin of the name is unknown. However, perhaps it was because someone saw the opportunity to label it with a tongue-in-cheek reference to some of the illicit activities that could take place. By the 1930’s the name “Virgin Lane” stuck and was officially referred to as such on maps, in the local newspaper, in City Ordinances, City directories, and the United States Censuses. The name was used continuously for about 80 years.

Virgin Lane was occupied by African American working-class people. Scattered amongst these dwellings were some buildings and houses that doubled as juke joints, small stores, bootleggers, and some “self-employed” ladies. Many railroad workers lived in this neighborhood and many other occupants were employed by the laundries, hotels, cafes, and stores that surrounded the area. Addresses were often listed as “123 Virgin Lane Rear,” as some of the houses were not on actual streets but rather dirt inroads or footpaths. Examination of the U. S. census records for 1920, 1930, and 1940 show that Virgin Lane was also home to some Chinese immigrants who opened grocery stores on Sharpe Avenue. In the surrounding area, many homes were occupied by people of Italian, Russian, Polish, Greek, German, and English descent. The censuses provide a “written picture” of the ethnically diverse population there. If the Mississippi Delta, Cleveland included, is its own smaller version of the American “melting pot,” then it could be argued that for a time, this area called Virgin Lane was a microcosm of the diverse and unique Delta populace.

Some of what is known about this place can be gleaned from oral histories where descriptions of rowdy Saturday nights include freshly-paid workers adding to the mix of drinking bootleg whiskey, gambling, and the often-referenced and seemingly overlooked by the law, “ladies of the night” along with a background of music. Although not well-documented, it is easy to understand that if the early Delta Bluesmen played in Cleveland, they most likely played Virgin Lane. Honeyboy Edwards of Shaw was quoted as saying of Cleveland, “It was an open town; it was gambling all night and day.”

There are many references to Charley Patton, Willie Brown and other early Delta Bluesmen living in Cleveland. There is plenty of information pointing to their residency in Virgin Lane, at least at some point. For instance, Charley Patton was married several times, once to Minnie Toy who had a daughter named China Lou. There are several Toys listed as residents of Virgin Lane, but Minnie is not documented in Cleveland until later, but China Lou is. Earl Harris is reported to have taught Patton guitar. Virgin Lane resident Pink Miller may or may not be the Pink Miller who often accompanied Patton. More than one Willie Brown lived there. Which one might be “friend boy Willie Brown,” reported to have been born in Cleveland in 1900?

The rowdier side of Virgin Lane is only one facet of the neighborhood. For many, it was simply home. Some had legitimate goods and services to offer, albeit out of poorly constructed buildings. More than one actual rocket scientist was born and raised for a while in a metal shed in Virgin Lane. On the edges, there were churches alongside white-owned bars. A Greek-owned pool hall was alongside an Italian grocery alongside a Jewish merchant. And it is quite probable that more than one Blues artist we celebrate today lived in Virgin Lane, as well.

Maybe the fact of Virgin Lane was accidental—an area formed by the engineering of streets—but it was an integrated, accepted part of a then largely segregated town for roughly 80 years. But Cleveland, like the nation, found itself undergoing sweeping cultural changes in the 1960’s. The Civil Rights era legislation shown a light on unfair practices regarding housing and basic city services. By 1970 Cleveland obtained a large HUD grant and better housing became available. The residents of Virgin Lane found measures of prosperity and opportunities to leave the aging rudimentary housing. In 1970, Virgin Lane became the target of both the city leaders and the Beautification Commission which had embarked on an all-encompassing city-wide clean-up program. Most of the remaining structures were demolished and parking lots to alleviate the overcrowded parking on Sharpe Avenue took their place. To encourage use, a breezeway was built between the parking lots and the main street. The alley itself was renamed Kamien Way in honor of longtime merchants, the Kamien family.

Recently, a marker was installed on Virgin Lane to commemorate what was. A Breezeway Committee, established by Mayor Billy Nowell, has been at work for some time on having the Breezeway remodeled and although progress has been made, it is not finished. Much appreciation should be given to the City of Cleveland, the Cleveland Heritage Commission, the City Beautification Commission, the Bolivar County Historical Society, the Delta State Archives and Museum and the Mississippi Department of Archives and History for the Virgin Lane marker.

On a final note, a marker documenting the existence of a place called Virgin Lane speaks to the growth of Cleveland and the recognition that preservation is an integral part of progress.