In the 1950s and 1960s, “Mr. Willard’s” was the hot spot in town.

Its name was the Shelby Drug Store. But, everyone called it Willard’s. I called him daddy. Perched at old U.S. 61 and Broadway, it was the sort of place you just don’t see anymore. An old-fashioned soda fountain with a marble counter, cluttered at one end with Nabs, Milky Ways, Snickers, Baby Ruths, potato chips and colorful packets of Topps baseball cards, the kind with a thin flat sheet of pink bubble gum inside.

Behind the counter was a freezer packed with ice cream— peach, chocolate, vanilla, strawberry, chocolate marble. Overlooking everything was a huge mirror, partly obscured by an ancient cash register, soft drink cups and milk shake mixer. At one end of the counter was a red cooler with the coldest bottled Cokes in town. At the other end was a big wooden display case of cigars. Across the store, behind round tables and wooden chairs, there were other counters and cabinets holding watches, electric razors, makeup, perfume, medicines and mysterious products like asafetida.

Up front, close to the big windows where the Ole Miss football schedule hung, there was a table packed with knick-knacks, a magazine rack with everything from True Detective to Redbook and a rotating comic book rack. A kid could grab a “funny book” and plop down on the cool concrete tile to read. Today, if kids did that, they’d be run out of modern stores.

There was no Walmart, no mall, no department store. Cell phones, texting and email were unheard of. People actually enjoyed talking to each other.

So, Willard’s was the social heart of the town. Everyone rolled through, especially on Saturdays.

It is hard for people to understand it today, but there was a mystical allure to the place. If you were near, it drew you in.

After last bell, school kids flooded in. “Mr. Willard, can I have a cherry Coke?” In seconds, daddy shot syrup into a cup, tossed in crushed ice, added carbonated water, a splash of cherry, then stirred at blinding speed with a spoon. Best Coke you ever tasted.

He whipped up banana splits and ice cream sodas with gobs of chocolate streaming down the sides and a cherry on top. If you pushed him, he could grab a scoop, toss ice cream in the air and catch it in the cone. Voila! I left many a scoop on the floor trying that trick.

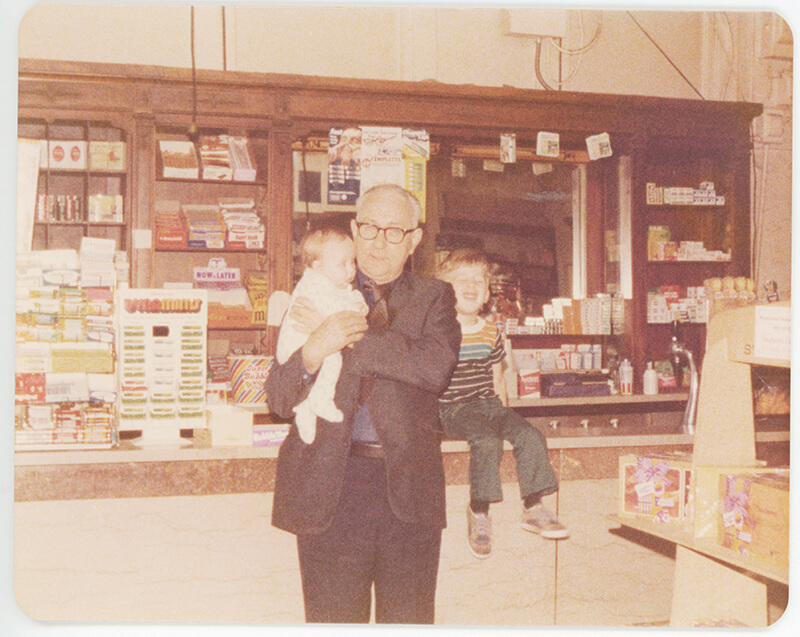

Willard gave the place much of its magic. He could talk to anybody and within five minutes he knew everything about them and they were friends for life. He had a big bark, especially when kids didn’t say “sir” or “Mister,” but he was all heart and everybody knew that. He instinctively knew when to unleash his thunderous laugh, when to joke, when to commiserate, when to be respectful, when to insist. Whatever social skills I have were learned watching him deal with customers. He dealt so well that, improbably, that little store paid to send three children to Ole Miss.

Adults came in to catch up on gossip, debate politics, soak up air conditioning or, in winter, the big open-faced heater at the rear. On Saturday nights, men gathered by the radio to listen to the Ole Miss Rebels. If it was close in the fourth quarter, daddy locked the door and we sat in the dark, listening to the Cajuns howl in Tiger Stadium as the Rebs battled LSU. I often think it was more fun that way than watching it on TV.

It was small town magic at its best, a camaraderie and a sense of comfort, safety and belonging hard to explain to those who never experienced it.

You could feel the town’s pulse, learn who was sick or dead, hear a good joke, assess the cotton crop, buy a newspaper. In times of stress, its familiar rhythms allowed people to breathe, to laugh. It was a fantasy land, a feel good place where relaxing came easy. As a teenager, I couldn’t see that. Older now, I see it clearly.

I grew up in there, learning from conversation, marveling at the intricacy, innocence and honesty of small town life.

I’d watch men hurry in late to buy True Detective or Sport, razor blades, medicine and, in Christmas season, a last-minute gift to avoid a wife’s wrath.

Dr. W.W. McKenzie, who played against the legendary Four Horsemen in college, would walk in to buy cigars and spot me sprawled on the floor reading the sports pages. He’d quiz me on Ted Williams’ batting average, Mickey Mantle’s homers, Warren Spahn’s record. His voice sounded like a growl, but he was a warm, kind man who quietly paid to send needy kids to college.

Women came for makeup, perfume, lipstick. Daddy was somehow an expert on that, too.

The store was my hiding place. At ten, I was so small and skinny that I could wriggle through sliding doors at the back of the cigar counter. There in the darkness, breathing in the distinctive aroma, I’d use cigar boxes for a pillow and steal a nap with my dog Sputnik. Daddy would reach in there for a box of cigars and grab a handful of me or, worse, the dog.

Travelers wandered in and sat silently until daddy would grin and ask, “Where you from?” Before you knew it, they were sharing family tales.

The drug store was like that. It turned strangers into friends, made the shy talk.

Daddy died in 1979. Today, only a concrete slab remains. When it shut its doors for the last time, I couldn’t help thinking that I was watching the death of a time and a place. And something else. The death of my childhood.

Bill Rose, who grew up in Shelby, enjoyed a long career in the newspaper business. Most of his years were spent in leadership positions at the Miami Herald in Miami, Florida. A few years ago, he retired and lives in Oxford, Mississippi.

By Bill Rose

The Bolivar Bullet